The Art Of Choosing Iyengar Pdf Editor

The Art Of Choosing Summary. She’s one of the world’s most prominent researchers in this field and conductor of the famous jam study, in which shoppers could sample either 6 or 24 different varieties of jam at a grocery store, which led to six times more purchases when less jams were available.

Belief in one’s ability to exert control over the environment and to produce desired results is essential for an individual’s well being. It has been repeatedly argued that the perception of control is not only desirable, but it is likely a psychological and biological necessity. In this article, we review the literature supporting this claim and present evidence for a biological basis for the need for control and for choice — that is, the means by which we exercise control over the environment. Converging evidence from animal research, clinical studies, and neuroimaging work suggest that the need for control is a biological imperative for survival, and a corticostriatal network is implicated as the neural substrate of this adaptive behavior. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel—American children’s book writer and cartoonist) From Western philosophical and psychological theory to government constitutions and beloved children’s books, we are immersed in a vocabulary of “personal freedom” and “self-determination.” An important question is whether this societal emphasis is the cause or the consequence of the need to exercise personal autonomy. Some may argue that people feel entitled to be their own “deciders,” that is, to exercise personal autonomy, as a result of societal values that are acquired through social learning. However, converging evidence from diverse areas of research provide increasing support for a biological explanation for our need for control.

Individuals exercise control over the environment by making choices. These choices include complex and emotionally salient decisions that may occur only once in a lifetime (e.g. Which university to attend), but also include basic perceptual decisions that occur hundreds of thousands of times every day (e.g. Deciding where to focus your attention in the visual field).

Although much of our behavior is elicited by environmental cues, and may be below the state of explicit awareness, all voluntary behavior involves choice nonetheless. Thus, to choose, is to express a preference, and to assert the self. Each choice – no matter how small – reinforces the perception of control and self-efficacy (see ), and removing choice likely undermines this adaptive belief. Choice is the vehicle for exercising control. (Left panel) For a given goal state, there is a desired outcome. When an individual chooses actions that lead to the desired outcome, the experienced contingency results in the perception of control. Although there is extensive evidence that the perception of control is adaptive across diverse spheres of psychosocial functioning as well as physical health (see below), there have been no attempts to integrate these findings into a systematic review addressing why people desire choice and control.

Here, we present evidence to support the claim that the need for control is biologically motivated, meaning that the biological bases for this need have been adaptively selected for evolutionary survival. First, we summarize the predominant contributions to our understanding of perceived control and its adaptive effects.

We then present empirical evidence that the presence or absence of control has a profound impact on the regulation of emotion, cognition, and physiology. Finally, we examine the neural substrates of the need for control based on findings from animal studies, clinical populations, and neuroimaging research. Taken together, this evidence provides compelling support for a biological explanation of the need for choice. Choice is a Vehicle for Perceiving Control If people did not believe they were capable of successfully producing desired results, there would be very little incentive to face even the slightest challenge. Thus, perception of control is likely adaptive for survival.

The benefits of control beliefs have been reviewed extensively , though less attention has been paid to understanding the benefits of behaviorally exercising control (but see ). Opportunities to exercise control may be necessary to foster self-efficacy beliefs. Individuals with little experience of acting as an effective agent will likely have little belief in their ability to produce desired results, leading to feelings of helplessness and depression. Text Box 1Perceiving Control: Key Terms The perception that one is “in control” is a complex psychological phenomenon whose many facets have been described using various terms. Albert Bandura has used terms such as “agency” and “self-efficacy” to describe the collective beliefs in one’s abilities to exert control over one’s environment and to act as an agent capable of producing desired results.

A high sense of self-efficacy supports the construction of anticipation and beliefs of successful performance, and actual success on the anticipated task further strengthens beliefs of efficacy. In addition, research has shown that the stronger the perceived self-efficacy, the higher the goals people set for themselves. An extensive literature suggests that perceived self-efficacy is highly adaptive in many areas of psychosocial functioning, including work-related performance, psychosocial functioning in children and adolescents, academic achievement and persistence, and health functioning.

Constructs related to self-efficacy have been proposed by others. Julian Rotter coined the term “locus of control” to refer to an individual’s belief that life events are within personal control (internal locus of control), as opposed to a belief that events are uncontrollable (external locus of control).

Ellen Langer demonstrated the phenomenon of “illusion of control,” which is the assumption of personal control when there is no true control over the situation or event (e.g. Believing you have a better chance of winning the lottery if you select the lucky numbers). More recently, Deci and Ryan have argued that “autonomy” and “self-determination”– terms describing an individual’s motivation to act as an independent and causal agent upon the environment – are fundamental psychological needs. While the theories behind each term have conceptual differences, they largely address the same underlying phenomenon and reach a common conclusion: the belief in one’s ability to exert control over the environment and to produce desired results is essential for an individual’s general well being. Opportunities for choice have been shown to create the illusion of control (see ).

For example, healthy individuals tend to overestimate their personal control and ability to achieve success in chance situations involving choice, whereas depressed individuals are more accurate in judging the degree of personal control. When attempts to control events are unsuccessful, healthy individuals tend to rationalize outcomes rather than admit any compromise of personal control,. The findings of such research suggest that the illusion of control may protect individuals against the development of maladaptive cognitive and affective responses. Additionally, the default assumption of control by healthy individuals when provided with opportunity for choice suggests that the assumption of control is adaptive. Violation of this assumption may result in abnormal behavior and compromised functioning. Individuals who do not perceive control over their environments may seek to gain control in any way possible, potentially engaging in maladaptive behaviors. Furthermore, while the illusion of control seems to be adaptive for psychosocial functioning, extreme overestimates of control may contribute to dangerous risk-taking,.

Struggles to augment or diminish control are believed to be at the core of anxiety and mood disorders, eating disorders, and substance abuse. Therapeutic treatments from diverse theoretical perspectives focus on issues of control to promote patients’ well being. Ultimately, the automatic perception of control seems to be essential for healthy functioning, whereas disruptions to perceived control can result in various manifestations of psychopathology.

Choice is Desirable Choice allows organisms to exert control over the environment by selecting behaviors that are conducive to achieving desirable outcomes and avoiding undesirable outcomes. As a result, one would expect that opportunities to exercise choice would be desirable, in and of themselves (see ). In fact, animals and humans alike demonstrate a preference for choice over non-choice, even when that choice affords no improvement in outcome reward. For example, it has been found that when deciding between two options, animals, and humans, prefer the option that leads to a second choice over one that does not, even though the expected value of both options is the same, and making a second choice requires greater expenditure of energy. In economic terms, the preference for choice and control in such conditions may be considered irrational.

Yet, if we consider that exercising control could be rewarding in and of itself, then such behavior could be considered rational for maximizing utility. People report that tasks involving choice, however inconsequential, are more enjoyable than tasks without choice, and the provision of choice often leads to improved performance on a task.

In a classic study by Langer & Rodin, even having a single opportunity to exercise choice was shown to influence subsequent mood, quality of life, and longevity in nursing-home residents. It seems that choice can induce greater feelings of confidence and success, which likely further reinforces choice behavior and efficacy beliefs. Collectively, these findings imply that choice is rewarding per se. In fact, simply expressing a preference, through choice, may reinforce an individual’s perception of control if choices are perceived as optimal for producing desired results. In an early variant of the now classic “free-choice” paradigm , subjects rated their liking for eight appliances and then decided which of two similarly rated appliances they would like to own. Subsequent ratings of all appliances showed that subjects tended to rate the chosen appliance higher and the rejected appliance lower than they had initially.

This and many similar results established that choice can motivate attitude change, and spawned theories of post-choice rationalization and self-perception as processes that enacted the changes. More recent work suggests, however, that the subjective optimization of choice outcomes is a natural, and relatively automatic, byproduct of choice.

Restriction of Choice is Aversive The argument for an inherent need for control is strengthened by the findings of physiological and behavioral detriments when personal control is absent. In animals and humans, the perception of control over a stressor has been shown to inhibit autonomic arousal, stress hormone release, immune system suppression, and maladaptive behaviors (e.g. Learned helplessness) observed when stressors are uncontrollable,. Behavioral control has been implicated in decreasing arousal during anticipation of aversive photographs, and in increasing tolerance to pain and aversive noise. The benefits of perceived control can exist even in the absence of true control over aversive events, or if the individual has the opportunity to exert control but never actually exercises that option. Thus, the perception of control seems to be important for regulation of emotional responses to stressful situations.

In the absence of other stressors, however, the removal of choice, in and of itself, can be very stressful. It has been found that restriction of behaviors, particularly behaviors that are highly valued by a species, contributes to behavioral and physiological manifestations of stress,. In fact, physical restraint is one of the most popular methods for experimentally inducing stress in rodents. While this procedure does not physically harm the animals in any way, the simple restriction of motion nonetheless results in robust behavioral and physiological indices of stress, such as increased heart rate, increased norepinephrine and cortisol release, and the production of gastric ulcers. On a similar note, animals raised in captivity are markedly disadvantaged compared to their free-ranging conspecifics.

Lack of control over the environment is believed to be a major cause of the abnormal stereotypic behaviors, failure to thrive and impaired reproduction commonly observed in animals raised in captivity. It seems that the aversive effects of captivity may depend on the extent to which behavioral choices have been reduced relative to what could be performed in the natural environment.

When animals are provided access to an additional region of their habitat, they show a significant reduction in the stress-related stereotypic behaviors commonly observed in captive animals (e.g. Pacing), increased social play, and decreased levels of the stress-hormone cortisol,. Furthermore, species with larger natural home-range size tend to have higher frequencies of stereotypic behaviors and higher rates of infant mortality, but this relationship applies only to animals in captivity, and not for their free-ranging conspecifics. Humans demonstrate similar patterns of negative affect in response to the removal or restriction of choices. Once control over an aversive stimulus has been established, the removal of this control produces greater fear, more negative perceptions of the stimulus, narrowing of attention, and greater effort placed on regaining control. Negative responses to losing control have been observed even in very young human infants. In four-month old infants, disrupting a learned contingency between behavior and rewards, results in negative emotional reactions, even if rewards are still delivered, but are not dependent on the infants’ actions.

Additionally, once children master a skill (e.g. Feeding themselves), they become resistant to adult attempts to influence or control this ability. The preference for control, and aversion to its removal, observed in very young infants, suggests that these preferences may be present at birth, or at least very early in development, and thus likely reflect a fundamental need that is biologically motivated.

Neural Bases of Choice and Control: Implications for Emotion Regulation To make our case for a biological basis for the need for control, we have provided evidence that the perception of control is adaptive, that choice is desirable, and that the removal of choice is aversive. While the behavioral evidence is compelling on its own, it is critical that we identify potential biological substrates of choice and control. The evidence described above suggests that perceived control influences cognition and behavior by modulating affective and motivational processing.

Thus, we would expect that the experience of control, as it is exercised through choice, would engage primarily brain regions that have been associated with emotion processing and regulation. Though the affective experience of choice itself has not been examined directly, there is converging evidence that implicates a corticostriatal network as the neural substrate for perceiving control (see ). Hypothesized Neural Circuitry for Choice The prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the striatum are known to be highly interconnected and have been implicated consistently in affective and motivational processes,. Certain regions within this corticostriatal network explicitly code for actions that are most adaptive in a given context. For example, a subset of neurons in the monkey striatum respond to the expected value of a specific action (e.g. Choose left vs. Choose right), but do not predict the magnitude of potential rewards, or the probability of selecting of an action, independent of its reward outcome.

This suggests that there is a biological basis for organisms to be causal agents, rather than passive observers, in their interactions with the environment. The exercise of choice allows organisms to select behaviors that will optimize rewards and minimize punishments, or at least to perceive such effectiveness. Below, we describe evidence from the extant literature supporting the striatum and PFC as key neural substrates of this adaptive behavior.

Recent neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that choice recruits neural circuitry involved in reward and motivation processing. For example, rewards that are instrumentally delivered activate the striatum to a greater extent than rewards that are passively received,. In an emotional oddball task, Tricomi and colleagues found that rewards following choices activated the striatum to a greater extent than the same rewards following responses where no choice was available. Participants in that study reported feeling greater control over the monetary outcomes when choice was available.

Increased activity in the striatum as a function of choice observed by Tricomi and others may reflect increased motivational incentive under choice conditions. Increased activity in the dorsal striatum is also observed when there is greater motivational incentive to perform a task or in response to highly salient stimuli. If free choice preferentially activates the striatum, a region involved in reward processing and goal-directed behavior, we might hypothesize that choice, itself, may be inherently rewarding.

In stressful situations, perceived control may modulate emotion by reducing negative affect. Though it is adaptive to automatically generate emotional responses to threats in the environment, it is necessary for an individual to appropriately modulate those responses for the given context. The PFC likely plays an important role in the exertion of top-down regulation of emotional responses,. Work by Maier and colleagues has been critical for understanding the neural bases of controllability effects on stress regulation. In their work, Maier et al found that rodents typically demonstrate stress-related behavior and physiological response when faced with uncontrollable stress (inescapable shock) but not when faced with controllable stress (escapable shock). They found that the relationship between stressor controllability and reduced stress response is mediated by increased activity in the medial PFC (MPFC).

Subsequent experiments demonstrated that if the MPFC is lesioned or deactivated, rats respond to escapable shock as if it is inescapable,. Additionally, they found that if the MPFC is stimulated during inescapable shock, rats demonstrate a reduced stress response. Thus, the protective effects of controllability depend on the integrity and activity of the MPFC.

The rodent MPFC functionally overlaps with both the medial and lateral portions of the primate PFC, regions that have been implicated in perception of control in recent neuroimaging studies. The perception of control in the absence of any true control has been associated with increased activity in the MPFC. Additionally, there is evidence that recruitment of the lateral and medial PFC when exercising control may mitigate negative emotional responses to aversive situations, such as pain, and choices involving increased risk. These findings are consistent with results demonstrating an inverse relationship between PFC activity and limbic activity (i.e. Amygdala) during both the downregulation of negative affect and fear extinction,. Thus, in threatening situations, the opportunity to exercise control may alleviate stress by engaging MPFC mechanisms of emotion modulation.

In fact, individuals with major depression fail to normally recruit ventral portions of the MPFC when attempting to downregulate negative affect. Control-related activity in the MPFC may also reflect behaviors associated with increased self-relevance, since the MPFC is implicated in perception of the “self” –. Several studies have found the ventral MPFC to be preferentially active when making choices that are self-relevant (e.g. Preferences) as compared to choices involving only a perceptual discrimination,. Nearby regions of the ventrolateral PFC have been found to respond more to choices that have greater personal consequence. Thus, opportunity for choice may be more desirable because it engages self-processing networks that increase the subjective value of the actions and their associated rewards.

Above, we present evidence that regions in the PFC and striatum play important roles in perceiving control. It is likely that these regions form a corticostriatal network that interacts to produce the motivational states associated with control and choice. The PFC and striatum are highly interconnected and are commonly coactivated in studies of affective and motivational processes. Furthermore, disruption to motivation, or even complete apathy, can occur as a result of damage or disease of either the striatum or the PFC, suggesting the communication between these regions is critical for motivational processes. Disruptions to the perception of, and desire for control are also associated with alterations in functioning of the MPFC. Profound apathy accompanying Alzheimer’s disease is associated with reduced metabolic activity in the MPFC. Schizophrenic individuals with delusions of control and persecution show reduced activity in the ventral MPFC when assessing whether a threat is self-relevant.

These findings support the hypothesis that corticostriatal regions are involved in perceiving control. Moreover, they demonstrate that the desire for control is an essential component of what it means to be human, since the extreme compromise in this desire and in an individual’s sense of self is observed only in what are arguably some of the most devastating and debilitating psychiatric disorders. Caveats and Conclusions In this review, we present evidence that suggests the desire for control is not something we acquire through learning, but rather, is innate, and thus likely biologically motivated. We are born to choose.

The existence of the desire for control is present in animals and even very young infants before any societal or cultural values of autonomy can be learned. It is possible that organisms have adapted to find control rewarding – and its absence aversive – since the perception of control seems to play an important role in buffering an individual’s response to environmental stress. We propose that brain regions in a corticostriatal network are integral for the perception of control.

If the desire for control is imperative for survival, it makes sense that the neural bases of these adaptive behaviors would be in phylogenetically older regions of the brain that are involved in affective and motivational processes. Although we present evidence supporting a biological basis for the need for control, we do not make assumptions about the boundaries of the preference for control and choice (see ), nor do we claim that this preference is unchangeable. The desire for control is distinguishable from an individual’s experienced perception of control. While the basic need for control may be biologically motivated, it is possible, as well as probable, that the perception of control, and the preference to exert control, can be altered as a result of personal experience with control, as well as learning what is most rewarding in a social context, which may explain cultural differences in how choice is valued (see ). Nonetheless, personal autonomy seems to be highly valued in very young children from diverse cultures.

Exactly what content is perceived to be included in the personal domain may vary across cultures, but what is important cross-culturally is that the exercise of choice acts to energize and reinforce an individual’s sense of agency,. Anything that undermines this perception of control may be harmful to an individual’s well-being.

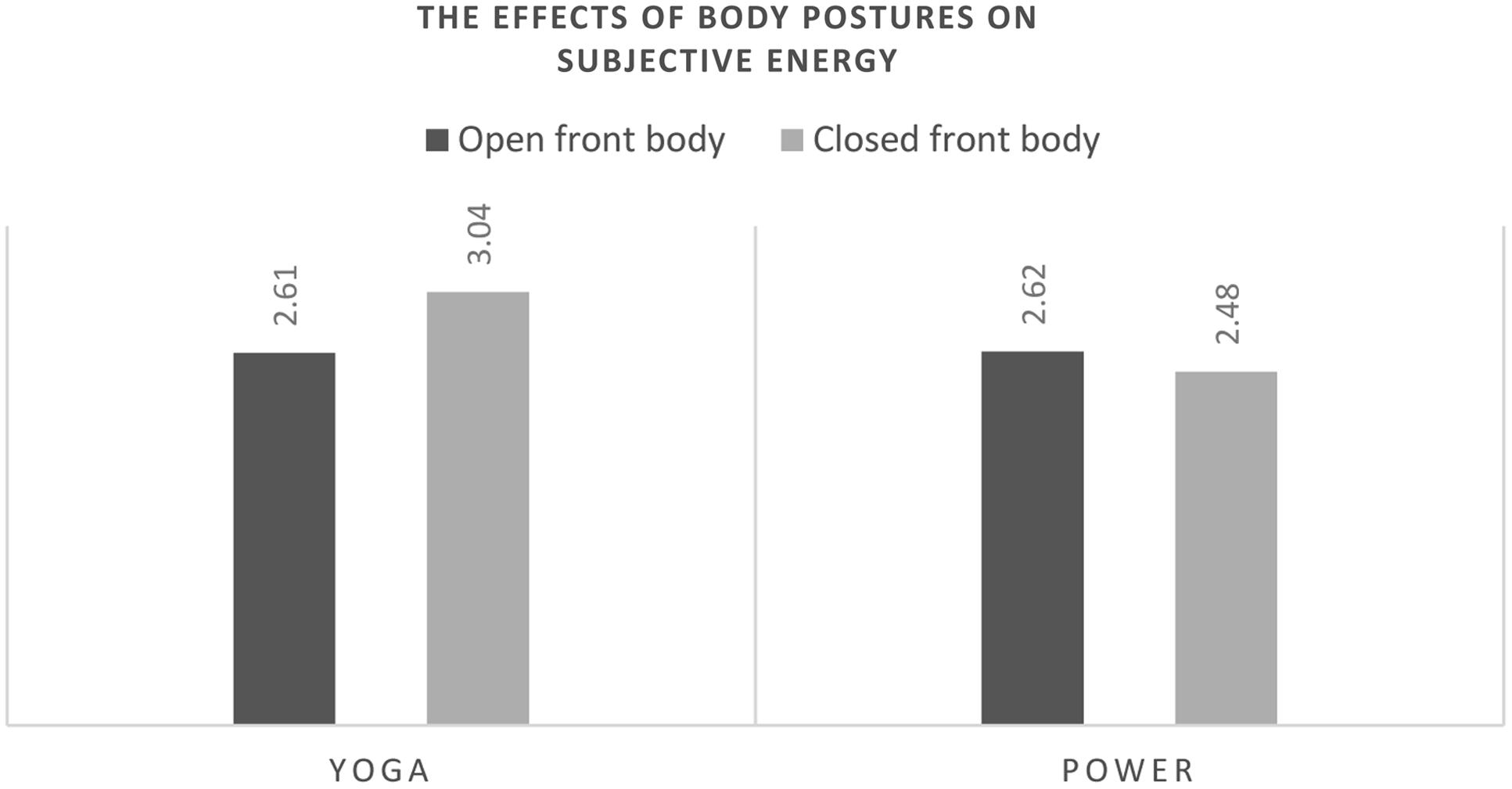

Text Box 2When is choice undesirable? Choice may not be desirable in all situations, particularly in the context of complex or emotionally difficult decisions. However, there may be a difference between the desire to have choices and the desire to make choices. For example, a study by Iyengar and Lepper found that found that although greater choices seem to be more attractive at first, a larger assortment ultimately may result in deferral of choice. In this study, individuals who were given the opportunity to select from an array of six gourmet jams were more likely to purchase a jam than were participants who chose from an array of 24 or 30 choices. Moreover, individuals were more satisfied with their selections when they were chosen from the limited array of options.

In a similar vein, a recent study investigating choice preferences in the context of healthcare found that of the 823 participants included in the study, 95.6% indicated that having choices was extremely important, whereas only 30.3% indicated that making choices was extremely important. If we are motivated to choose the best option, then choosing a non-optimal option means that we were unsuccessful, and so avoiding decision may reflect anticipatory regret or fear of failure or blame for poor decisions. This may explain why people tend to defer to default options (i.e. Status-quo) when choice difficulty is increased, a phenomenon which has recently been linked to connectivity between PFC and the basal ganglia. In the absence of sufficient knowledge or resources to make an optimal decision, choice by a proxy agent, such as a trusted friend, family member, or physician, may be more desirable than personal choice. In any case, individuals are still exercising control by choosing to engage in or to abstain from decisions to promote their best interest. How is the value of choice and exercising control impacted by individual differences in development, personality, learning history, and cultural experiences more broadly?

Collectively, the evidence suggests the desire to exercise control, and thus, the desire to make choices, is paramount for survival. The opportunity for choice enhances an individual’s perception of control, and thus, exercising choice may serve as the primary means by which humans and animals foster this psychologically adaptive belief. Just as we respond to physiological needs (e.g. Hunger) with specific behaviors (i.e.

Food consumption), we may fill a fundamental psychological need by exercising choice. While eating is undoubtedly necessary for survival, we argue that exercising control may be critical for an individual to thrive. Thus, we propose that exercising choice and the need for control – much like eating and hunger – are biologically motivated. We argue that while people may be biologically programmed to desire the opportunity for choice, the value of exercising specific choices likely depends on the available cognitive resources of the decision-maker in the given context, as well as the subjective value of the choice contents, influenced by personal experience and social and cultural learning. Expected value For a given variable (e.g. Monetary reward), the expected value is equal to the product of the actual value and its probability of occurring Learned helplessness When animals or humans have experienced uncontrollable stress they may display helpless behavior when presented with controllable stress in the future Post-choice rationalization Cognitive dissonance arises when one’s choices (or actions more generally) conflict with one’s prior attitudes about choice options.

This dissonant state is unpleasant and motivates a change in attitudes about what was chosen and/or not chosen (or done or not done, more generally), which serves to both justify the choice and reduce dissonance. Theory of self-perception Theory presented by Daryl Bem, which argues that people draw inferences about their attitudes or beliefs based on observations of their own behavior, rather than direct access to mental states.

The Art Of Choosing Iyengar Pdf Editor Free

Sheena Iyengar studies how we make choices - and how we feel about the The Art of Choosing has 4189 ratings and 368 reviews. Odai said: فقدت شيينا أينغار (مؤلفة الكتاب ) بصرها في عمر الخامسة عشر وهي التي جاءت من أبوين هندوس Sheena Iyengar studies how we make choices — and how we feel about the choices we make TED Talk Subtitles and Transcript: Sheena Iyengar studies how we make choices - and how we feel about the choices we make. At TEDGlobal, she talks about We all want customized experiences and products - but when faced with 700 options 26 Jul 2010 Sheena Iyengar studies how people choose (and what makes us think we're good at it). On the art of choosing: Sheena Iyengar on TED.com. A Mac store customer asks for the latest iPhone in black, but he sees everyone else buying black and suddenly changes his preference to white.

When a 17 Mar 2010 Sheena Iyengar, a blind writer on the psychology of choice, built a In “The Art of Choosing,” her first book, out this month, she presents the Whether mundane or life-altering, these choices define us and shape our lives. Sheena Iyengar asks the difficult questions about how and why we choose: Is the Sheena Iyengar studies how we make choices - and how we feel about the choices we make. At TEDGlobal, she talks about both trivial choices (Coke v.